Kicking off 2019 with an exciting bang, Grady Gammage, Jr. was featured in the Arizona Republic with a front page op-ed piece discussing the momentum of voting and the future of water policy in Arizona. Mr. Gammage suggests that 2018 may have been the year that determines Arizona’s future!

From the Arizona Republic:

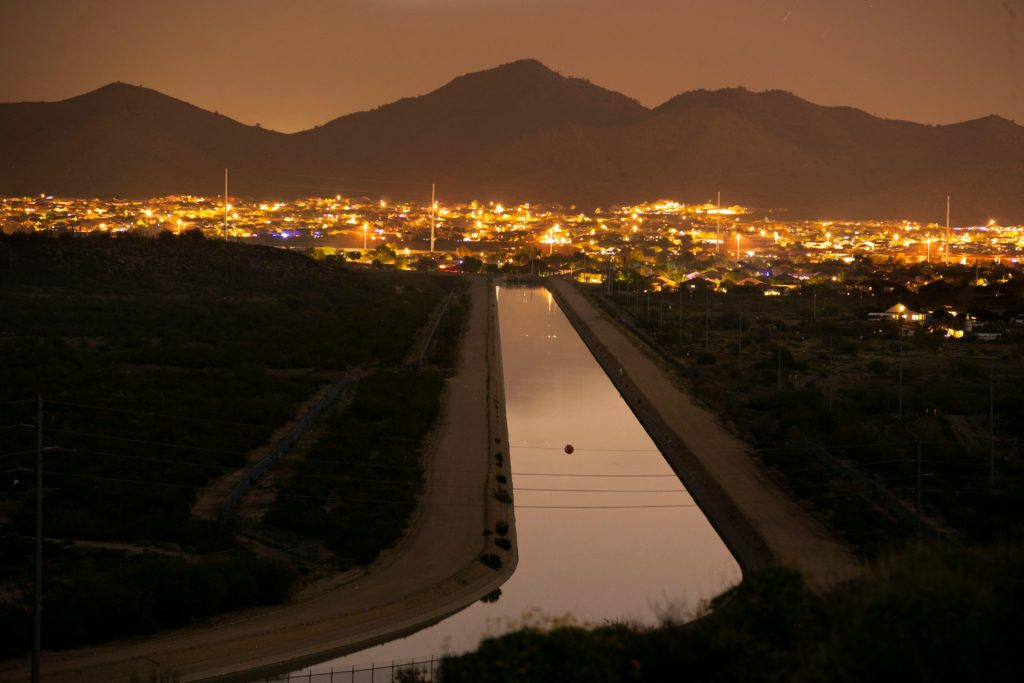

Photo from David Wallace/The Republic

2018 was a turning point for Arizona. Here’s how we make the most of it.

FROM HOW WE VOTE TO HOW WE TALK ABOUT WATER, 2018 MAY HAVE BEEN THE YEAR THAT DETERMINES ARIZONA’S FUTURE.

Odds are, you won’t know when you are in a watershed moment.

When you drive over the continental divide, at least there is a sign to tell you something major just passed. With points in time, you cannot tell how important something is until long enough afterward to gain some perspective.

There is also a high risk that you will think something represents a watershed when it turns out to be no big deal. Pronouncing a turning point is fraught with risk. But here it is: 2018 may well have been a watershed year in Arizona.

Arizona State University students wait in line to vote at the polling place at ASU’s Tempe campus on Nov. 6, 2018. (Photo: David Wallace/The Republic)

One sign is the recent election. In July, the Morrison Institute for Public Policy released a report examining Arizona’s abysmal record for voter participation. Then it turned out that voters were energized this year to a degree not seen in a long time. Photos of long lines of ASU students waiting to exercise their franchise repeatedly made the national news.

The second piece of evidence is that not only did Arizona voters participate, but they made discerning judgments. A pragmatic Republican governor was reelected by a wide margin, and yet, those same voters chose a Democrat for United States Senate: A Democrat who said she wanted to “get stuff done.”

Maybe this means electoral politics is becoming more moderate, more focused on results than on scoring philosophical points.

CHAPTER 1:

WHAT THE ELECTION MEANT

Arizona has been regarded as a reliably “red” state, meaning that it was conservative and generally Republican. This was not always the case. Arizona was born in a spasm of progressivism in the early 20th century, and there have been many significant Democratic politicians in the history of the state.

But for the past quarter century, Arizona has consistently been regarded as one of the reddest states in the union.

There are different shades of red in America. Texas is also considered deeply red (despite the excitement Beto O’Rourke created). Yet, Texas is different than Arizona. Texans are reliably and often obnoxiously impressed with themselves and their state.

It used to be an independent country. The hubris of Texans leads them to a shared understanding of what it means when they say, with a swagger, “We’re Texas.”

Texans recognize that their state is a joint enterprise to be managed for the mutual benefit of its citizens. They engage in relatively activist government, using incentives to promote business attraction and private sector jobs.

Another state just to our north is also a different shade of red. Utah’s redness is based in a clear cultural heritage. It was, after all, founded on the religious imperative of Brigham Young’s pronouncement, “This is the place.”

They act, not with a swagger, but with a quiet conviction. The clarity of that history gives Utah’s red a similar tint: an expectation that the shared enterprise borne out of historical antecedent is to be used for the benefit of those who live there.

WHAT ‘RED’ MEANS IN ARIZONA

Arizona’s red is different. We lack the shared culture of Texas or Utah. Arizona is more a rootless collection of migrants from elsewhere lured to live in a place because of sunshine and cheap land. As a consequence, Arizona’s shade of red has a less collective and more libertarian bent.

A Legislature comprised largely of people born elsewhere tends to view the state not as a shared enterprise, but as an intriguing experiment. Arizona is often an experiment in how little government we can get away with, how low revenues can be compressed and how much and how frequently taxes can be cut. We operate with neither a swagger nor quiet conviction, but rather with inconsistent and sometimes insecure policy decisions.

Arizona’s shade of red has a less collective and more libertarian bent. (Photo: Ronald J. Hansen/The Republic)

The central question of the entire American experience is surely, “What is government for?” How do we balance between desires of the individual and the needs of society? What collective actions must we take to maintain order? How do we sort the benefits and burdens of laws and regulations? How do we transact the social contract?

The United States presents a complex system for answering questions about the role of government, for it is the states that are the fundamental repositories of collective power. The states hold the general “police power” to protect, through law and regulation, the health, safety and welfare of its citizens.

For a state like Arizona, young, insecure and suspicious, answering the question about what collective actions should be taken by government on behalf of the entire citizenry is especially complicated. Bound by little shared culture and a thin layer of institutions, Arizona has been a place where the social contract is still under negotiation.

CHAPTER 2:

HOW WATER FITS IN

For all our state’s life we have had one strong, universal consensus about the clearest need for government action: to obtain, defend, manage, allocate and deliver water. A long history of pragmatic, non-partisan decisions to manage water supply was a necessity in a place as hot and dry as Arizona. Water management is the thing we have done best, because it is the clearest shared cultural value we have.

At the end of 2018, we have yet another sign of a potential watershed: a return to the realization that water management is a place for pragmatic governance designed to solve problems.

A consensus is emerging on approving a “drought contingency plan” (DCP) designed to save water in Lake Mead, and to allocate shortages of Colorado River water within Arizona.

How to distribute common resources, and how to share their shortage is a perennial conundrum of governance. That arriving at a consensus on the DCP has taken time and involved controversy is not a bad sign — it is a good sign that we still know how important water is to our identity and continuing existence.

WE’RE GETTING HOTTER AND DRIER

The most burning political question of our time is what to do about climate change. How to handle “the tragedy of the commons” is the question of what to do when a freely available public resource is over-exploited because no individual has sufficient incentive to modify his own behavior.

Overgrazing of a common pasture is the classic example, but a more current one is air pollution: I don’t want to stop burning my fireplace, and even if I did so it would make no difference to air pollution in Phoenix. So regulation affecting all fireplace users is necessary to achieve cleaner air.

Climate change is the global tragedy of the commons.

One city, one state, even one country is not sufficient to “fix” the greenhouse gas problem. The magnitude of the issue makes avoidance, delay or even denial a default choice.

For local places the question is not how to stop, or even how to mitigate climate change. The question is how to deal with it. For Arizona, the answer should be clear: We have done this before.

Hot and dry is what we know. Hotter and drier is a major challenge, but we should view our future through the lens of our history of water management. We are good at this. The future is one of climate management. We can be at the top of the list of doing this well.

CHAPTER 3:

CLIMATE CHANGE IS OUR NEXT BATTLE

It is not intuitively obvious that Arizona might be well positioned to deal with climate change. To many people, Phoenix is already at the ragged edge of habitability.

Conservationist and author William deBuys, for example, writing in the Los Angeles Timesin 2013 about the impending doom of climate change, offered: “If cities were stocks, you’d short Phoenix.”

He’s wrong.

Right now a number of California coastal cities are considering plans for something called “managed retreat” – how to abandon oceanside properties as sea level rises. Do owners get compensated for leaving their multi-million dollar homes? How are the costs spread? One beachfront mecca, Del Mar, has chosen to refuse any mention of retreat – concluding it might hurt their sky-high property values.

Or consider the likely effects of increased hurricanes on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts or tornadoes through the Midwest. How do those areas prepare to cope? Arizona suffers few catastrophic events. We will have more wildfires, but unlike California, they generally do not threaten major cities.

HOW UNSUSTAINABLE IS ARIZONA?

The simplistic view that Arizona is unsustainable is wrong: We are better positioned to cope with the challenges of climate change than most places. Our challenges will be slower moving:

- Higher temperatures lasting for longer periods;

- Nighttimes that do not cool off;

- Decreased and more irregular rainfall;

- Severely stressed forests in the north country;

- Lower reservoir levels and less runoff.

These are significant challenges, but there are known techniques to respond.

Arizona’s future requires a dramatic commitment to climate management equal to our historical expertise in water management. Water is part of that commitment:

- Increased conservation;

- More aggressive reuse;

- Deliberate thought about the future of agriculture;

- Exploration of desalinization.

Lifestyle modification plays a major role: less grass, more trees; fewer private swimming pools.

Urban design, too, is a piece: How do we build to mitigate the heat island? What is the appropriate use of water and landscape in community gathering spaces? How can we introduce more shade into the urban fabric?

Climate management also means thinking about even bigger questions. What is the appropriate density for cities in the desert? How will autonomous vehicles affect development patterns?

CHAPTER 4:

HOW ARIZONA CAN LEAD

Again, Arizona can be at the forefront of these trends. Solar and other alternative energy sources are another part of success – we have one of the largest solar footprints in the U.S. Coal generation is almost over in Arizona.

We are already doing a lot of these things. Besides moving on the drought contingency plan, the Arizona Department of Water Resources, Salt River Project and Central Arizona Project have been aggressively pursuing new water management techniques and the acquisition of additional resources.

The City of Phoenix has proposed a water rate increase specifically for the purpose of adding additional infrastructure to make groundwater resources more available and better distributed. (The proposal recently was voted down, but it will – and should – be back soon.)

Forest thinning has been stepped up in the last few years, reducing fuel and increasing watershed health.

The recently announced ASU/Piper Trust partnership dubbed “The Knowledge Exchange for Resilience” to study heat impact is an innovative research project squarely aimed at the issue.

The entire Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability is the most prominent example of ASU trying to get ahead of the curve.

YES, ARIZONA CAN GAIN FROM THIS

What we are not doing is realizing that these are all part of a piece: a response to increasing climate challenges. We should not be afraid of acknowledging that.

The culture of Arizona is built on the history of recognizing the special effort it takes to live in an often hostile desert environment. Our future should be built on explicitly defining ourselves as the place dealing most directly with the impacts of climate change.

We cannot allow others to call us, as Andrew Ross did in his 2011 book Bird on Fire, “the world’s least sustainable place.”

Does this mean we should exploit our position – benefiting from the near apocalyptic dilemma confronting the world? Yes, it does. We have always marketed our climate. We just need to adjust the pitch.

This is already happening with the increasing relocations of financial service and insurance business and call centers to Arizona – these companies are recognizing the relative absence of natural disasters when they choose to move here.

Metro Phoenix can become a logistical crossroads of the western U.S. as Interstate 11 links Mexico through Phoenix to Las Vegas and on north. Our relative insulation from catastrophic climate disasters will attract major employment opportunities so long as we thoughtfully plan the infrastructure needed to build the future.

CAN WE FIND OUR SWAGGER?

Grady Gammage Jr. outside Gammage Auditorium in Tempe on December 20, 2018. (Photo: Cheryl Evans/The Republic)

If 2018 turns out to be a watershed, it will not be simply because more people turned out to vote, or because those people made more discerning and discriminating decisions.

It will be because in doing so they came to realize the potential of Arizona.

It will be because they began to create a shared understanding of what this place is all about. Arizona has always used the power of government – collective action – to manage water supplies in a challenging and arid place.

Our past was all about managing water to make this place possible. Now our future must be all about managing climate to make it sustainable. In that activity may we find quiet confidence, and maybe a bit of a swagger.

Grady Gammage, Jr. is a practicing lawyer, a senior scholar at the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability and a senior fellow at the Morrison Institute.

Read the full Arizona Republic opinion from Grady Gammage, Jr. online here.